The artist Paul Brandford had an anxiety dream last night. He was late for something. Something important. But he didn’t know what. He just knew he was late. He had to catch a train from one red bricked Victorian station to another. Every time he was on the train, Brandford realised he was heading back to where he had started from. He was still late. And now he was lost.

He laughs the dream off. Fucking dreams. Fucking annoying dream. Just anxiety about getting up early on the days he teaches at college. An early start. Will the alarm go off? Will the trains be on time? Artists are dependent only on themselves and their talent, not on the intervention of extraneous circumstances.

Paul Brandford is a highly talented and original artist. He is among a group of British artists like Broughton and Birnie, Bensley and Dipré, Simon Leahy- Clark, Locky Morris and Alex Pearl who are “breaking the narrative” of British art.

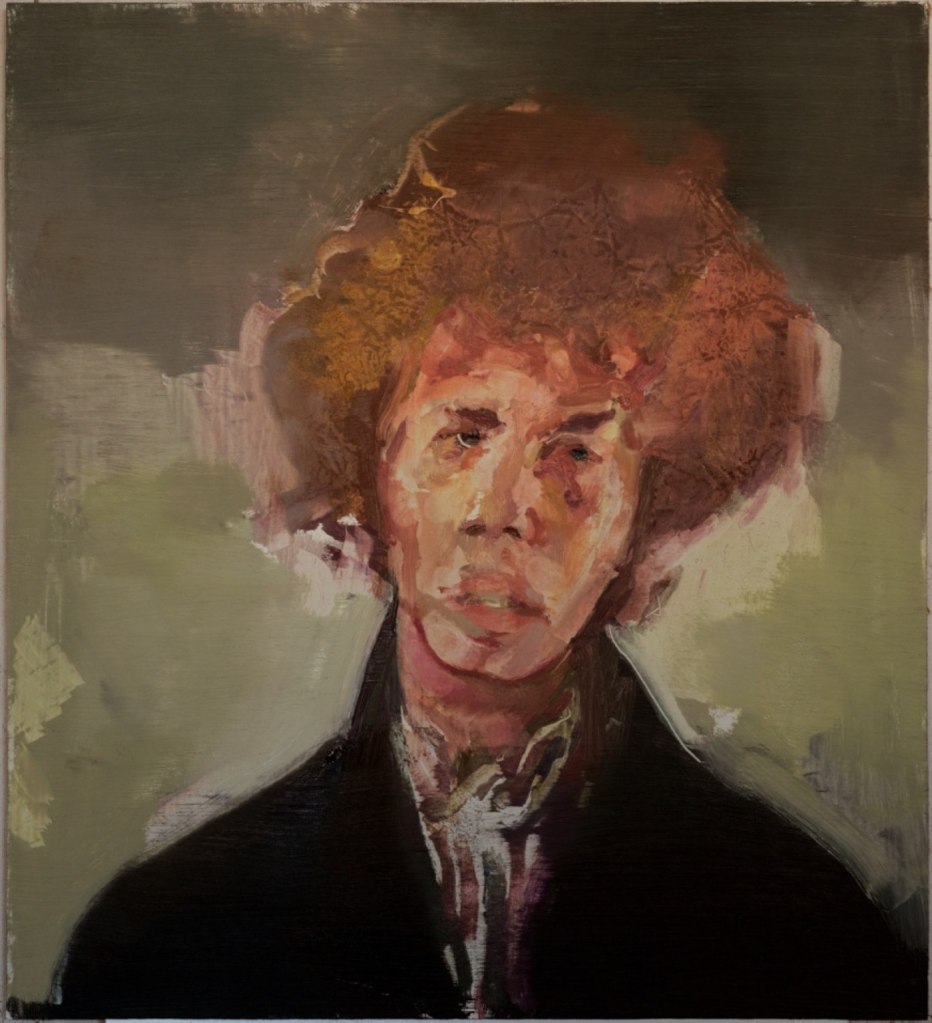

Brandford paints large pictures filled with figures culled from classical paintings and images swiped from social media. If as John Berger once wrote that Turner “best represents most fully the character of the British 19th century,” then Brandford best and most brilliantly represents Britain’s culture in the digital age and its endless, chaotic stream of images.

Today Brandford is working at his studio. The studio is in Hackney Wick. He shares it with his wife the artist Jeanette Barnes. But never at the same time.

“The actual making of a painting is not a spectator sport,” says Brandford. “All sorts of things, instinctive things, stupid things, inexplicable things go on. They’re done for the painting to become itself – not for the amusement of others. Being watched does inhibit behaviour. Painting – in my book – is a distinctly private and personal enterprise. Which is completely at odds with the notion that you then want everyone to look at it once it’s done. I’m not the first person to acknowledge that the whole thing is completely ridiculous.”

What are you working on today?

Paul Brandford: I’ve got plans for a painting based on derogatory photoshops that have been slung around twitter between people with some degree of creativity but nothing better to do with it. I like sourcing a subject by chance a lot of the time – it jars against themes that I’d naturally select to somehow energise an image.

How do you paint?

PB: I like to paint on a well primed board – it somehow enhances the physical aspect of paint and painting. Nothing soaks in – it’s all on the surface so that regardless of the illusion created the painting is also undeniably a thing. If I’m painting something from a collage – I’ll assemble the collage in a way that seems interesting and then draw it – maybe in charcoal, maybe in pastel and ink on quite a large scale to test if the collage is at all feasible on a much larger scale. I like to paint quickly and instinctively so that a decent amount of prep is essential to this.

If I’m painting something much smaller or want to be more spontaneous – I’ll just paint directly from the source without any prep. The big things take a few months from beginning to end, sometimes it’s good just to hack something out in a single day without too much thought or expectation.

When things aren’t going as you’d like or as you might have expected that actually creates an opportunity to develop what you’re doing in a new way – so it’s not all bad. The worse thing is when it’s going really well and you’re concerned about not spoiling the thing and you’ll fuck it up by being too careful.

How do you choose what you’re working on?

PB: I think the first attraction to a theme or subject has to be primarily visual. For some reason you like the look of a thing or the idea of what you might turn it into. It’s not a precise thing. There are always the odd things that you draw and paint that don’t seem to fit in with the rest of it, and that’s a good thing.

Themes go in cycles and invariably run their course, wars, politicians, film and television, glitches in communication. In a funny way the subjects occur and choose themselves. There does become a point though when more work on a subject or theme feels repetitious or safe in some way – when you know too much about what you’re going to do. Then it’s time to move on.

How do you start a painting?

PB: Quite traditionally in some ways – you have to make sure that on a large scale your design is going to fit but initially your sense of placement has to be flexible enough to allow for changes of mind – so big blocks of simple colour roughly where I think they should be. I avoid getting sucked into detail until a sense of the whole becomes more evident. On something smaller though I’d just do what I like – sometimes to break the habits of a fixed process. My paintings have been on board for about thirty years.

Tell me about your paintings of politicians?

PB: These started by chance – a strange photo of a politician in a newspaper. They’re constantly photographed meaning unguarded and awkward moments will be used by the press to ridicule or undermine.

PB: One of the earliest examples was not strictly a politician but Mark Thatcher – on trial in South Africa – the press were jabbing microphones right into his face as he left the court. The resulting photographs were comedic and provocative, which I enjoyed painting (almost as if there was some cross over with Carry On characters.

PB: I did a lot of Tony Blair, Pope Benedict, Boris Johnson (when he was London’s Mayor) and David Cameron – who’s distinctly odd shaped head took some while to get to grips with. In the earlier pictures I’d sometimes tread on them to agitate the surface with footprints and studio dirt. They were painted not on an easel but on the floor so that the image could take whatever physical treatment I came up with without falling over.

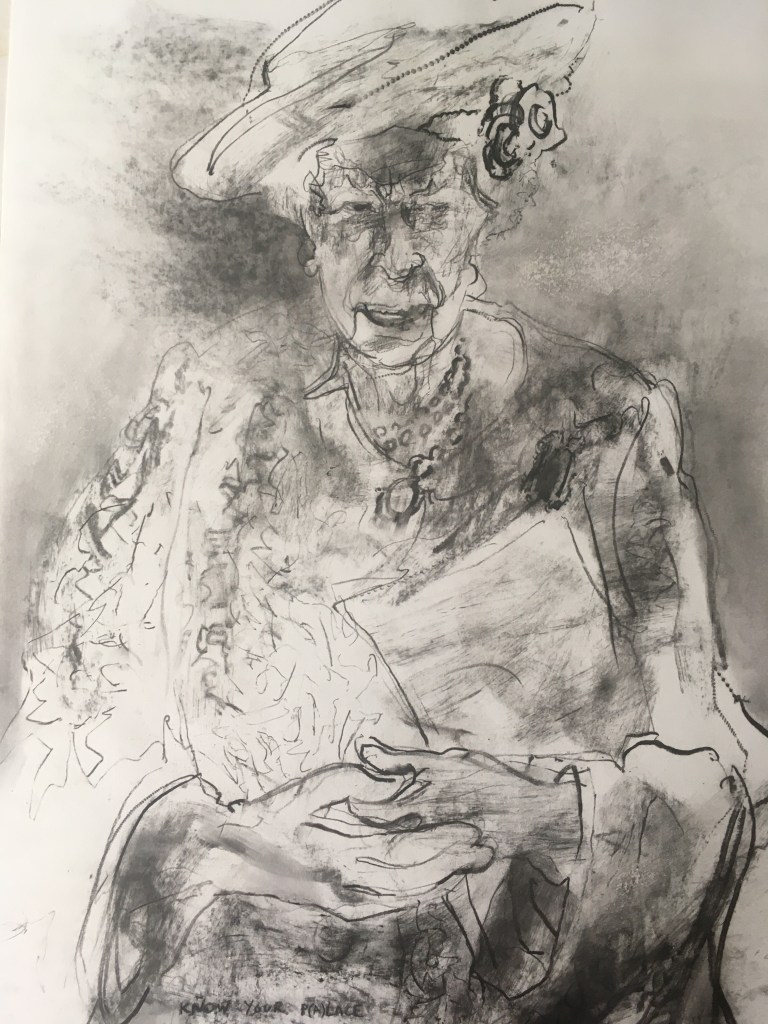

Tell me about your paintings of Royalty?

PB: My family were big royalists, me less so.

The idea that, like the politicians, you begin with something or someone recognisable to most people means that the manipulations, oddities and accidents will appear more pronounced and the image is about that as much as it is about the original subject. I also like playing about with the respect agenda – accept your place, know your betters. I wasn’t quite old enough to be a punk in the mid to late seventies, but I was old enough to see what it meant. There’s also so much scope to be had when dealing with uniforms – I have no intention of carefully rendering King Charles’s medals, I have every intention of splatting paint about to somehow degrade their supposed meaning or value.

Where do ‘Carry On’ films fit in with your work?

PB: Carry On films have always been there. I watched them as a little kid, I still watch them from time to time now – not that you’ll find them on the telly that much anymore.

The best ones are very well scripted and the timing of the delivery is excellent. The cast of characters – though I never much cared for Jim Dale (though Carry On Cowboy is very much underrated in my book) or Barbara Windsor but Sid James, Kenneth Williams and Joan Simms are fine comedy actors.

PB: As a kid I liked the idea that big schemes of pompous figures, powerful figures, could be undone by the little man or by chance occurrences. They were anarchic, disrespectful and anti-establishment in a playful way. Sid is always earthy, willing to ride his luck and take his pleasures where he can find them – he often finds himself in a senior (and uniformed) position which he clearly does not merit. Kenneth has grand airs, disliking anything physical or menial. He aspires to greatness, even from a privileged position, without having the means to satisfactorily attain his goals. He remains jealous and thwarted. The nature of us all is somehow captured by this dynamic between them both – the body and the mind perpetually working against each other.

When Sid James appears in a painting, it’s a sign that the viewer that the situation is inherently ridiculous and prone to unravel – especially when pertaining to war or conquest. The man in the uniform doesn’t buy into the value system that put him there.

What are your favourite movies?

PB: The films I’ve watched the most times in no particular order:

The Talented Mr Ripley, Carry On Up the Khyber, Carry On Cleo, Gladiator and In Bruges.

My favourite art films are The Rebel, The Final Portrait and Love is the Devil.

More recently I watched Sorry To Bother You- which I thought was incredibly imaginative without being over reliant upon fantasy..

I also enjoy zombie movies – I find them very relaxing.

Who are your comedy heroes?

PB: In the seventies Dave Allen and Leonard Rossiter really changed my view of what entertainment actually was. Anyone sitting through a pure diet of The Good Old Days, Mike Yarwood or Seaside Special (or was it Summertime Special?) would think that actual entertainment never existed.

Mel Brooks is massively innovative – my big picture with all the comedic figures from fake or reimagined history was inspired in a way by the end of Blazing Saddles where all the different actors from different film sets collide and a huge punch up ensues. That painting also comes from seeing vast Tintorettoes in Venice. Mine tries to deal with how the internet throws past, present and future, truths and falsehoods, the serious and the inane simultaneously at the user in a potentially overwhelming experience.

Stewart Lee has his critics but the way in which he can structure threads is impressive and in my opinion genuinely inventive.

I also very much liked the way that Bruce Forsyth used to bully the contestants at the start of The Generation Game. I learnt a lot from that.

You have said you ”want to make poetry from the conflict between authority and fear’’, can you explain this?

PB: My dad was a bit of an authoritarian bully when I was a kid, but that’s because he lacked the personal courage to be something else or to do something else. Paintings of dictators and politicians most probably are re-enactments of all that.

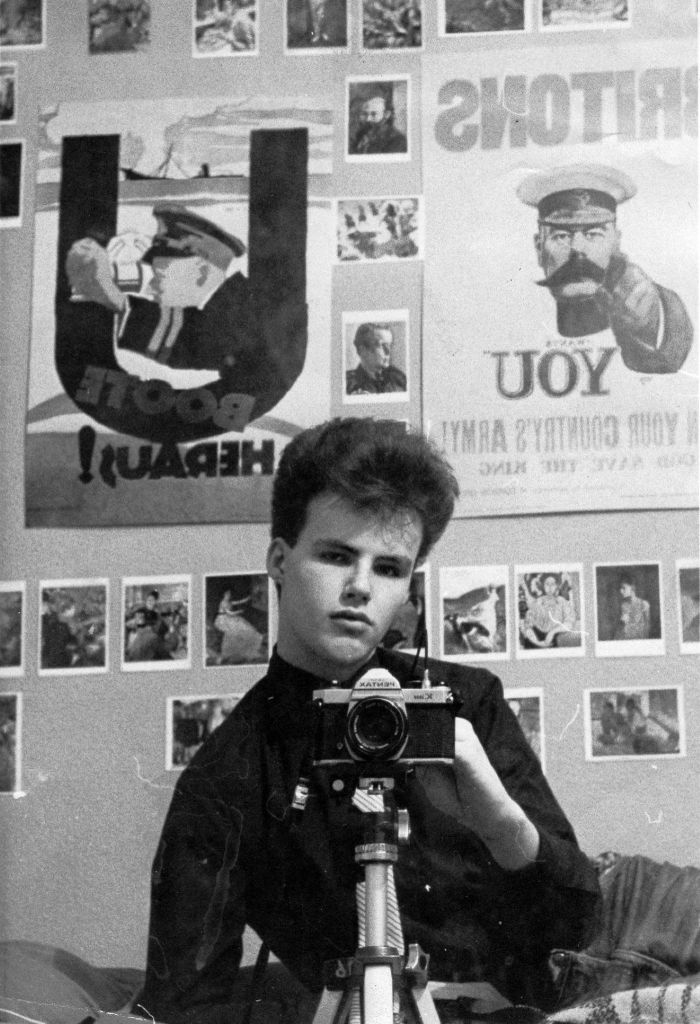

What’s your background? What compelled you to become an artist?

PB: My background is unremarkable in every way. Art was an escape from that.

My parents had nine to five jobs – I’d imagine they were unrewarding in every way but in the seventies people did what they did and so long as they could go to the work’s dinner – dance, have their week away in Clacton, have their suburban new build they didn’t think too deeply or ask too many questions. I knew that wasn’t for me from quite a young age. My parents wanted me to be an architect – the respectable face of creativity – or so they imagined.

Should art be moral?

PB: It really doesn’t have to be. People will see a thing and project their own values onto it regardless. Which is fine, if something is in the public domain – it’s theirs just as much as it’s yours.

Tell me about your British National Party (BNP) Youth Portraits? What was your intention? What was the response?

PB: My wife loves those paintings – the way that they’ve been made. They’re a few years old now but they’ve never been exhibited. I’m not sure that there’s much of an appetite to either show work like that these days.

It all began when someone sent me a video link on Twitter. It was a BNP electoral ad for the 2014 Euro elections. Kids barely out of school were reading a shockingly poor script featuring a tirade about the banking crash of 2008 and obviously immigration and a host of other perceived (or actual) unfairness crippling Britain at the time and how the BNP were the best hope for a new future. The production values were poor. The kids involved didn’t deliver their lines too well, collars were tucked into a jumper on one side, pulled out on the other. The thing that really interested me (I was as a theme concerned with the idea of artworks that no one would want on their walls at the time) was that at seventeen these kids were at the junction between childhood and adulthood. My brother at that time in his life got into heavy metal and then Christianity and quite quickly out of them – in the search for identity and belonging I suppose. Identity is up for grabs when you’re seventeen. So we’ve got these kids making these statements. Do they believe what they’re saying? Will they grow into being something or someone else. The film catches them at a transitional moment doing something that’s pretty far out. I do know that the kid who spoke with the most confidence got sent down subsequently for involvement in some sort of far right terror plot, one of the girls was apparently Nick Griffin’s daughter – but I don’t know which one.

PB: The portraits are trying to show a bunch of seventeen year olds without giving too much away. It’s the title that then sets the viewer’s mind to work. The original video was pulled from YouTube several years ago.

Do critics fail artists?

PB: Art critics, in my opinion, hardly exist these days. People around long enough to have insight and experience, open minded enough to understand meaning within the new. Most critics don’t criticize, they’re more like feature writers, an extended PR department. With such an overwhelming diversity of art practice currently available it’s hard to blame them to be fair.

I probably have more issue with curators. Artists seem to have become a lumpen chaotic mass which can only be made sense of by way of curatorial intervention. Curators have become akin to DJs to some extent. More important than those who actually create the music.

Curatorship is important – I’ve done it myself but they’ve skewed the game by putting their agendas, their catalogue essays in pole position. That sense of raw visual encounter is undermined by their academic priorities.

How long do you spend in the studio?

PB: Depending on what I’m up to. Big paintings need serious commitment time wise. Smaller things less so.

I’ve never gone to the studio every day as if it was a nine to five. You have bursts of activity rather than endless slog.

Once you’re there you’d want to put in a decent six, seven or eight hours – otherwise the journey’s a bit pointless. Sometimes you think you’re about to go home and find yourself still there a couple of hours later. If things aren’t going well creatively Jeanette and I tell each other to stay in the room like Eddie Morra at the start of Limitless.

With thanks to Paul Brandford.

All images copyright Paul Brandford, used by kind permission.

Buy Jeanette Barnes & Paul Brandford’s book ‘City Sketching Reimagined’ here.

Leave a reply to john butler Cancel reply