Way, way back, many centuries ago…when I first worked as a director in TV there was a saying often bandied about by film crews when anything went wrong on a shoot: ‘Don’t worry, you can always fix it in the edit.’ This may have a different meaning now but back then it meant if you had an excess of unwieldy footage it could be whittled down into the most succinct of content by the editor. If an interviewee continuously ummed or ahed their way through an interminably meandering interview your editor could sharpen their words into the most pertinent of answers.

A good editor can make average content good and good content brilliant.

The best editing is not a craft, it is an art form. You never notice the best editing because it flows seamlessly like a piece of beautiful music.

The best editing makes the audience focus solely on the story being told.

Angela Slaven is one of the very best film and television editors working today.

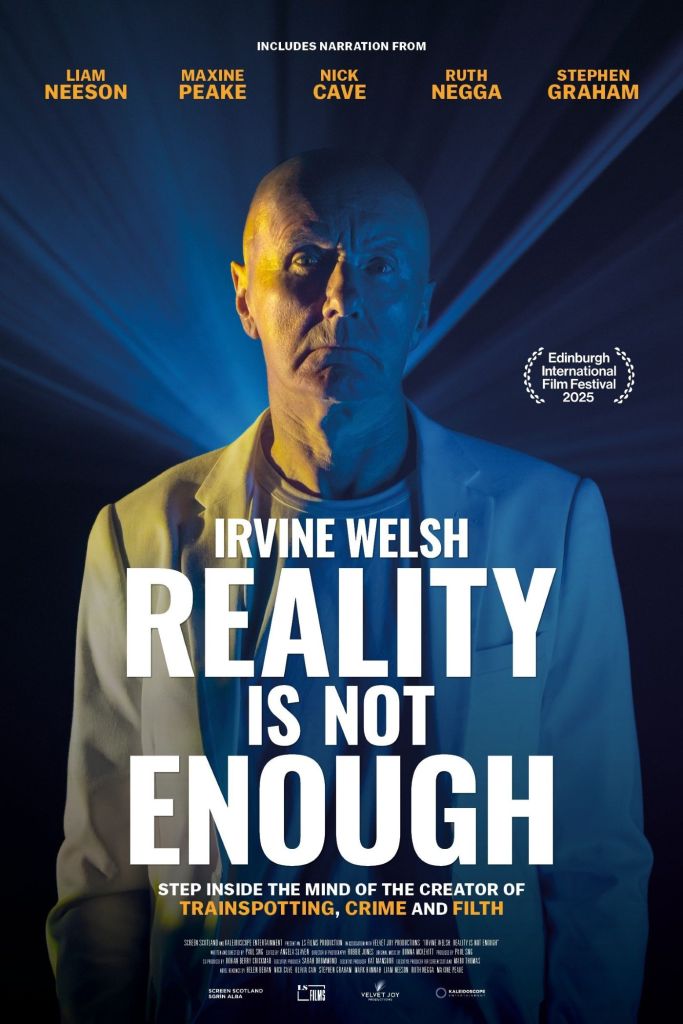

Born in Glasgow, Slaven started her career working in the Mail Room at Scottish Television. From such a seemingly unpromising beginning, Slaven made the move into post-production as an Assistant Editor where she learnt her craft and soon proved her unique talents as an editor. This led to Slaven cutting highly successful series like Taggart, High Times and Skint. Then moving into documentaries editing Michael Prince’s film on author John Irving and then his superb film on photographer Brian Griffin before working on Grant McPhee’s award winning documentary films Big Gold Dream and Teenage Superstars which focussed on Scotland’s post-Punk music scene. More recently Slaven has edited films on the Pet Shop Boys, Ivor Cutler and worked with Paul Sng editing in conjunction with Lindsay Watson his documentary on photographer Tish Murtha and cutting his film Irvine Welsh: Reality is Not Enough.

Tell me about your background.

Angela Slaven: I grew up as an only child in Glasgow, in Yoker on the boundary with Clydebank, and came from a railway family. The prevailing soundtrack was Mantovani and the Spanish and Italian eps my parents had bought on their holidays, journeying around Europe courtesy of their discounted railway passes.

AS: I was a bit of a tomboy, loved trainsets and cars and always had my nose in a book. Although my mum had to give up work when I came along, she would sometimes take part-time jobs, for example in Lewis’s at Christmas (therefore she knew the real Santa, not the fake Goldbergs or Frasers ones!). When she and my Dad were working, my Papa who lived close by in Clydebank would take me over to the Clydeside with Bobby the next door dog, where we’d play football on the old railway lines at the Rothesay Dock in the shadow of Yoker power station, stash the ball under an old railway sleeper then have a milky coffee and a buttered roll with chocolate buttons at the local café Pelosi’s near the Renfrew Ferry.

What did you want to be when you were growing up and what attracted you to becoming an editor?

AS: My dream jobs would either to have been an architect or a writer/journalist, but my creative writing skills were average and I wasn’t great at maths. I studied English Literature and Film and Television at Glasgow University and as part of the film course had to make a short film on videotape. Ours was called The Princess and the P – no spoilers but the P turned out to be the letter P written on a scrap of paper which blows away at the end, for some reason. But it was when we got to the editing stage that I had a kind of eureka moment, realising the possibilities of manipulating sound and pictures separately. This sounds like stating the bleeding obvious, but I hadn’t really grasped the power of it till being involved in the rudimentary video we were making.

What films or TV series which inspired you? What about directors or editors?

AS: I do remember late one night, perched on the arm of the chair nearest the TV, switching the set on and O, Lucky Man! had just started. I was riveted (uncomfortably) to that spot for the entire duration of the film. So that was an inspiration. I love Hitchcock, Powell and Pressburger, Lynch, all the usual suspects. But I hugely admire films where the sound design is really bold. I’m thinking of films like All the President’s Men, where music is used sparingly but very effectively. I love music, and I love working with music and sound design in films, it’s my favourite part of the process, but I don’t like music being overused which happens a lot. It’s like an additional character, making a statement or punctuating a thought or adding a layer of unease or happiness or whatever, and loses a lot of power if overused.

How did you start your career?

AS: Synchronicity is everything really. I temped for a while after graduating, and as luck would have it was sent to Scottish Television to work in the Mail Room. It was so showbizzy then – Arthur Montford would say hello when he passed in the corridor, imagine! And the place was dominated by the PAs, a troupe of formidably glamorous women who had a corridor all to themselves. Think Lauren Bacall, Kathleen Turner, Sophia Lauren and you’ll get the idea. But I basically hounded the editors, sitting in with them whenever possible, and one of them recommended I call the Head of Post Production at the BBC, John Grove. As luck would have it, I called on the Friday and a job syncing up film rushes had just become available, and so I started in the portacabin at the back of the old BBC building in Queen Margaret Drive – alongside now renowned Scottish film editor Colin Monie who I’d been at Uni with – where squirrels played on the roof.

I can still remember the smell of the polish in the lift when I would be ferrying the film cans on the way to the cutting rooms, which were arranged in a circle around a turret. It was magical. I think the first drama I worked on was with wonderful film editor Dave Harvie on a single play called These Foolish Things, starring Lindsay Duncan and James Fox. I had the grand title of Second Assistant which generally involved making tea, hiding under the trim bins when a viewing was in progress to be as inconspicuous as possible, and learning to love whisky when the Bowmore appeared from the filing cabinet late on a Friday afternoon. All very useful life skills. This particular play was directed by Charlie Gormley and produced by Andy Park – they were a great double act, very funny and very generous. We’d occasionally all jump in a cab and go to Babbity’s or the Caprese in Buchanan St for lunch on their tab, very exotic for a newly ex-student like me used to eking out my grant in the Grosvenor Café. Those days were an education in many ways.

You worked as a dubbing editor – what does this mean and what does the

work entail?

AS: A dubbing editor – well, you can get away with ropey pictures but not really with ropey sound, so dubbing editors are key. The role is usually called Sound Designer now. There are different areas of expertise within the scope of the job, depending on the scale and budget of the production.

For example the Dialogue editor will smooth out recorded dialogue, replace takes if something is unclear or background noise interferes, oversee additional dialogue recording (ADR).

The FX editor will layer up different sound FX, background atmospheres, creating a unique soundscape from thousands of different sources, often recording sounds if necessary to enrich the soundtrack.

The foley editor will supervise a foley session which involves the live recording of footsteps and sound FX to mimic what you’re watching onscreen, from spectacles being lifted up and pages turned, to stabbing cabbages to simulate gory murder scenes (as seen notably in Berberian Sound Studio, but Taggart was way ahead of the curve!).

I was incredibly lucky on a couple of occasions as an assistant dubbing editor to work with the mighty ‘Beryl the Boot’, I think it was on a 1997 Hallmark film called The Ruby Ring which starred Rutger Hauer, Judy Parfitt, and a lot of horses. Beryl Mortimer was a legendary foley artist ( she’d worked on Lawrence of Arabia!) and specialised in equine scenes, so she was brought up from London by our sound designer Douglas MacDougall, strode into the dubbing theatre with immaculately coiffed hair and a fetching white pants suit, and opened her case which contained an array of chains, leather belts and handcuffs to simulate the reins and bridles; coconuts to simulate the larger horses, and ‘donkey nuts’ for the smaller ones. I can only imagine what the customs man at Glasgow airport must have thought if he’d opened it up.

As an aside, I was also an assistant editor on that film, working with John Gow the editor of Gregory’s Girl which was and remains one of my very favourite films, so that was a treat.

How do you work as an editor? What is the difference between scripted programmes and documentaries? How do you navigate each?

AS: I’ve worked on both scripted and unscripted, and both are very challenging in different ways. In drama you’re working with a script, and although the structure can change sometimes radically from the original premise, there is at least a framework to get started with. With a doc, yes sometimes there will be a shooting script and a general outline of how the film might take shape, and a director with great ideas, but sometimes there is just a huge pile of material and a vague suggestion of how it might take form. It’s a bit like having a jigsaw with no picture, many of the pieces missing and quite a few thrown in from another puzzle altogether.

In both forms there is a huge amount of input required from the editor in terms of structuring and pacing the programme or film, as much responsibility as you want to take on really. Obviously, this is slightly dictated by who you’re working with, but most directors are extremely collaborative and very happy for someone to have fresh eyes on the material after the shoot, which can be an intense and stressful time. The cutting room is often like a therapy room, and a large percentage of the job can be counselling. What happens in the cutting room stays in the cutting room!

But what both of these forms have in common is the massive impact that the placing of music and sound design have on the rhythm of what you’re putting together. In the edit the editor is often responsible for choosing what the music is and for deciding where it goes, so I spend a lot of time sourcing music, whether commercial or library music, or if the budget allows, working with composers, and this is the most creative part of the process for me. An example would be Undisputed: the Life and Times of Ken Buchanan, about champion Scottish boxer Ken Buchanan, directed by Brian Ross. For a while I was pondering what would work musically for the fight scenes – didn’t want to do classical, too Raging Bull. Rock would be too…Rocky! Ken’s parents loved ballroom dancing, so I kept coming back to that and thinking about different types of dance music, and it was when I tried some big band jazz (Louis Prima style), it suddenly clicked. We were so chuffed on behalf of Ken to win an RTS Award for that in 2022.

What are your decision processes when editing? How do you know when to cut?

AS: Synchronicity again! Sometimes it’s accidental, something unintentional will happen and you think, ooh that works. Sometimes it takes hours of tweaking sound and pictures and music, it’s really not a spectator sport. I saw editing legend Thelma Schoonmaker answer this question last year during an interview, in which she was asked this three times. The first two times she patiently explained how she’d watch sequences over and over to get a feel for them, she’d think ‘Hmmm, needs a bit more of a pause here, less of a pause there, too long now, too short now’, make tiny adjustments etc. The third time she was asked she just said ‘It’s my job’! I did love that because it’s quite hard to explain, it really is just a case of getting a feel for the sequence, and once you have a version you feel can be watched in one go rather than scrutinising frames here and there, literally standing back from the screen to see it objectively as a viewer, and trying not to let all the other many choices you could make intrude.

Would you tell me about the hugely successful and long-running detective series editing ‘Taggart’? How did you become involved in this series and how did you work as an editor?

AS: I’ve worked over three decades, starting on film then videotape then nonlinear (Avid) editing. A couple of years after I started at BBC Scotland, I was offered a permanent job as an assistant at the BBC OUPC (Open University Production Centre), so moved to Milton Keynes for three or so years. It was a great place to work, but I was desperate to get back home. I would watch Taggart to get my Glasgow fix and dream about working on it one day, which did seem pretty impossible to be honest. Anyway, I remember very vividly on Children in Need day 1993 I got a call from Bob Dowie, head of post at STV at the time, to offer me a job back in Glasgow, so I leapt at the chance. After a while I worked my way up to dubbing editor, while Mark McManus was still the lead, and then editor on Taggart, which felt a bit unreal.

Although I work mainly on docs now I did originally work more on drama, but recently cut a series called Skint, 8×15 min short films on a theme of poverty. I’d worked with producer Carolynne Sinclair Kidd years before on a series called High Times, a very funny counter cultural comedy drama which won BAFTA for best series in 2004. Skint was mostly written and sometimes directed by people who hadn’t been involved with TV before. It involved a great cast of actors, including the likes of Michael Socha, Saoirse Monica-Jackson and Peter Mullan. And great writers and directors, amongst them Cora Bissett, Jenni Fagan, James Price, Lisa McGee. This happened during the latter stages of covid so I worked home alone, sending cuts to the directors. The schedule was one week per film; essentially a couple of days to look at rushes and pull together a rough cut, find music, send to director, then work on notes, refine, get the time down and have the film signed off on day 5. It was a tight turnaround but I loved this project, it was so interesting to work with different people/different styles one after the other like that.

The impetus to work more on documentaries came about when I went down to London in 2003 to cut an observational doc called Don’t Drop the Coffin, set in an undertaker’s business in Bermondsey. The characters were fascinating, the subject matter was sensitive, and it was the first time I’d been up to my elbows in an ob-doc series so I got a real taste for it. I love working on Arts and Social History docs especially, and have made quite a few for the BBC with Independent Producer Maurice Smith and the same team of female directors (eg Sarah Howitt, Shruti Rao, Margaret Shankland, Alison Pinkney), Directors of Photography and assistant and archive producers, who are just brilliant, intuitive and practical.

One doc in particular is a favourite of mine – Six Weeks to Save the World (directed by Sarah Howitt in 2018) which charted the phenomenal reach of American evangelist preacher Billy Graham as he took up residency at the Kelvin Hall in Glasgow for six weeks in 1955. I remember my Mum telling me that my Uncle and my Gran had been there, she was in fact in the choir. There is a lot of archive footage from the event, which I scoured, and did in fact spot my Gran! Composer Kenny Inglis composed a wonderfully atmospheric score for this programme. We had a few long chats about the sort of Boards of Canada-y analogue-y sense of disquiet that might work and it really did.

AS: Two other programmes I’d mention in particular are Artworks: Michael Clark’s Heroes. directed by Michael Prince in 2009, which followed enfant terrible post punk ballet dancer Michael Clark in the year where he was presenting a David Bowie- based performance both at the Venice Biennale and the Edinburgh Festival, and a doc I made with Director Alison Pinkney in 2018 for Sky Arts, Ivor Cutler by KT Tunstall.

I’ve worked with Michael many times and I think the first thing we made was a doc about Franz Ferdinand. He shoots beautifully and is also a great Stills photographer, but the best thing about him is that he’s always questioning things. Each morning he comes in and the first thing he says is ‘are we missing a trick here?’ So we’d go back and interrogate how we’d structured such and such a piece. No complacency. And we also got into trouble for laughing too much from the adjacent cutting room!

AS: I normally dislike watching anything I’ve worked on as I can always see things I should have done better, but one favourite edit is in this programme. There’s a scene where we go to Venice where the Bowie choreography is happening. Michael Clark visits Stravinsky’s grave in San Michele cemetery, over which we hear Rite of Spring. Then over a few shots of Venice and London we’re back to the London rehearsal room. I couldn’t quite get the transition to work, then all of a sudden I could hear in my head the Aladdin Sane music emerging from the Stravinsky, and that’s what made the transition. I realise it’s not as impressive as editing a flashy opening montage for a Bond film but it pleased me! Later on I worked with Michael on a film he made about the brilliant photographer Brian Griffin, The Surreal Lives of Brian Griffin.

AS: Brian was a great subject as he was quite intense, idiosyncratic, very funny and hugely talented. Strangely he also features in the film I’m working on just now, ‘The Revolutionary Spirit’, about the Liverpool music scene of the late 70s/80s, as he was famed for his record covers including those for Echo and the Bunnymen and the Teardrop Explodes. I’m so glad Michael had the foresight and determination to make that film as Brian died unexpectedly last year and is hugely missed, what a talent.

AS: The Ivor Cutler doc came about because I’d earlier worked with director Alison Pinkney on a film called Team Tibet, a passion project she’d filmed while working in India on another project. While there she’d met some Tibetan exiles who were setting up their own amateur Olympic team as they were banned from playing in the Beijing Olympics that year, so she filmed this off her own bat, along with producer Shruti Rao, a translator and small crew. They did a beautiful job and it’s a very moving film. Obviously quite difficult to film and work on something in a language you don’t speak, although we had onscreen subtitles, and that presented a few challenges as it was difficult to cut down until we could get hold of a translator who could guide us through the syntax and ensure things still made sense. Anyway, it played in festivals worldwide, winning the Best Self-Funded Film at Cine Pobre in 2019. As the Chinese Government take a dim view of any supporters of Tibet, we did wonder if we should change our names for the credits (we didn’t), but googled what our anagrams would be – as I recollect, I was Elven Lasagna and she was Insanely Pinko, a name which stuck!

AS: The Ivor Cutler doc we went on to do was presented by KT Tunstall, and included interviews with Ivor’s son Dan, his old BBC producer Piers Plowman, and his wife Phyllis. As a fan of Ivor – and someone who had timidly gone up to him back in the 80s at the Edinburgh Book Festival to say ‘Hello Mr Cutler’ and been given one of his famous stickers – it was a dream to do. I didn’t know much about KT but she was a true fan, a brilliant interviewer, genuinely interested in all the people who appeared and sang Ivor’s songs beautifully, guided by Alison’s very sensitive direction. It went on to be nominated for a Scottish BAFTA, and as Alison is pretty shy, I ended up at a Q&A at the BFI in London talking about Ivor as part of the Eccentric Miscellany Festival in 2023.

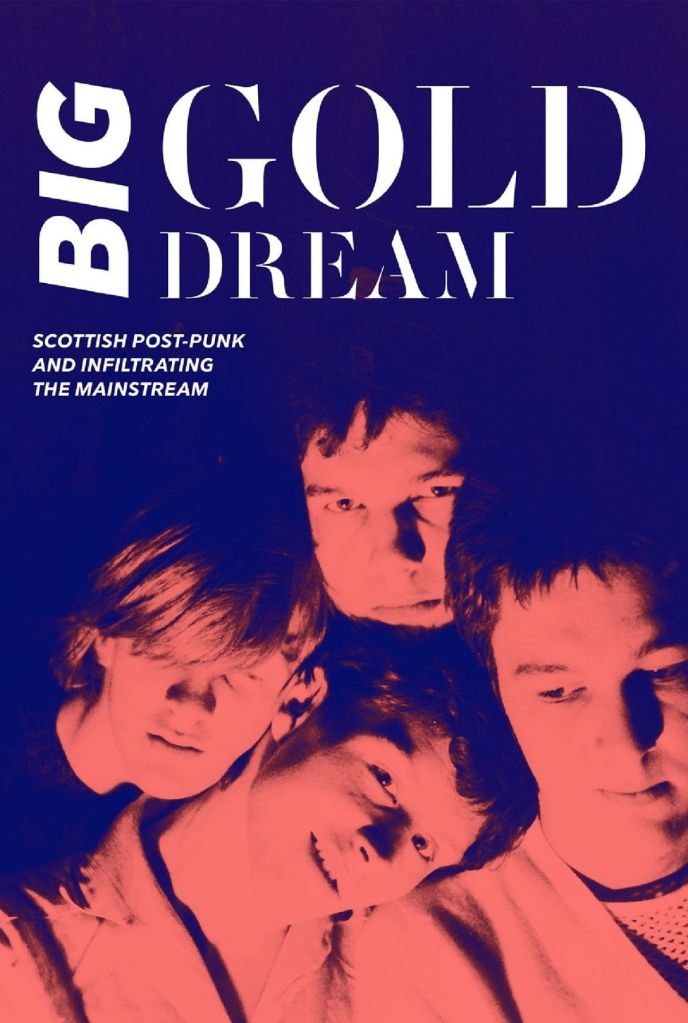

You made two music documentaries with Grant McPhee ‘Big Gold Dream’ and ‘Teenage Superstars’ in which you were editor as well as writer and co-producer. How did this come about?

AS: After working on the Brian Griffin and Tibet films, I started getting more into indie filmmaking (aka no budget and you do it in your own time because you love it). A great director friend of mine Becky Brazil put me in touch with Grant McPhee, as she knew I’m a massive music fan and I came of age musically speaking with many of the bands featured in Big Gold Dream; Josef K, Fire Engines, Orange Juice, the Associates etc. So when Grant outlined the project to me, I was in! It was a huge privilege for me to sit there going through hours of interviews with the likes of the spectacularly funny Davy Henderson, Malcolm Ross, Alan Rankine, Paul Research, Thurston Moore, Douglas Hart and so on.

AS: I didn’t at the time realise quite what a huge undertaking it would be in that so many people had already been interviewed – I think in the end there were 70+ interviewees for what turned out to be two feature length docs. It’s a lot of material a) to go through, b) to work out a structure for, and c) to find archive for. Also of course a huge difference when you’re used to working with a bigger team and there are people responsible for scripting, archive and music research, etc, but this was just the two of us until producer Wendy Griffin came on board, working remotely; me sending cuts to Grant and trying to whittle things down and him sending notes back.

But Grant is an amazing archivist and has the collector’s gene, he doesn’t rest until he’s unearthed every scrap of evidence and spoken to every person relating to a story, and is great at pointing up any inconsistencies or areas that need greater attention, that I might miss.

I did accidentally end up writing the VO for the films though. Writing is not my forte so I kept it as minimal as possible, imagining that a professional would be brought on at some point to reshape it properly. But that never happened! So I had the pleasure/pain of hearing the Go-Betweens’ Robert Forster and the Pixies’ Kim Deal reading the words wot I wrote, in true Ernie Wise style. Big Gold Dream went on to win the Audience Award at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2015, which was completely unexpected and amazing, so I guess we must have struck a chord somehow (no pun intended!).

You worked with Jim Burns on ‘It’s Not All Rock ’n’ Roll’ – how did this come about?

AS: Grant knew Jim was looking for an editor for his follow up to Serious Drugs and put us in touch. Jim invited me round to look at some of the rushes for the doc, about US/German band Swearing at Motorists fronted by extrovert singer Dave Doughman – sending me a brilliant little hand drawn map from the train station to his flat, which intrigued me right away. As soon as I saw the material I absolutely loved it. He has such a great eye and is very lateral thinking and therefore very insightful and inventive. He’d followed this band in Germany and over to the States on a road trip, filming everything himself. We went over to Hamburg to show the film to Dave before anyone else saw it, and screened it in the St Pauli stadium as he’s a huge St Pauli fan. It was quite emotional, I don’t think he knew what to expect.

How difficult is it to get programmes commissioned and made? Has the process changed

over the years? How? Why?

AS: It’s becoming very difficult to get programmes commissioned/films made nowadays. Broadcasters like to play safe, they tend not to go for single docs, as there’s more return on a series. The arts seems to be a dirty word. Funding for films is so difficult to get; there’s just less money around. It’s becoming more frequent that you almost have to make the film as proof of concept in order to attract funding, which means it takes a long time as you still have to do your day job to earn money.

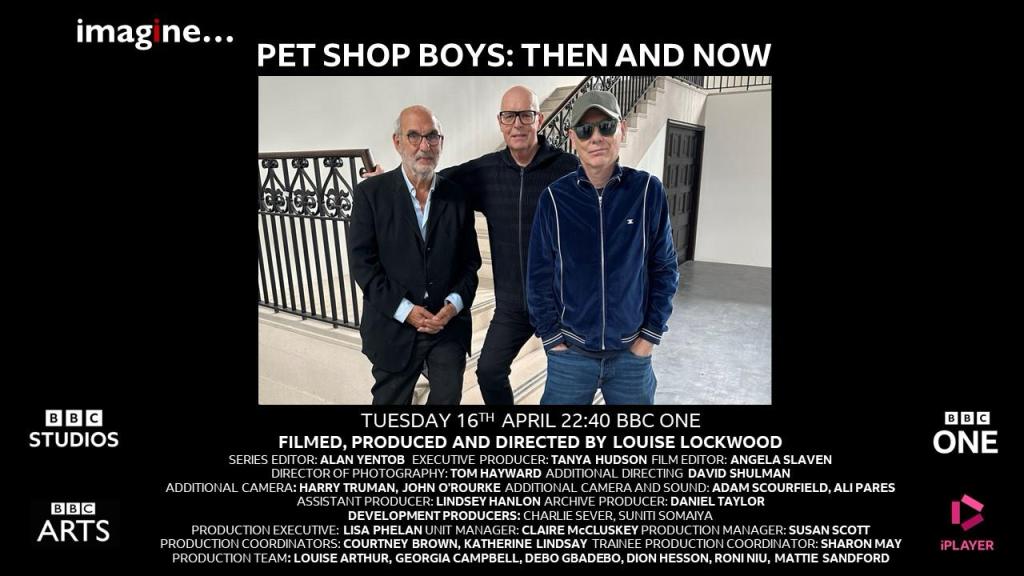

Next came a brilliant documentary on the Pet Shop Boys. What was that like?

AS: I am a huge fan of the PSBs so was delighted to be asked to make this film, particularly since the director was Lou Lockwood who is terrific and I’d wanted to work with her for ages. I was worried that maybe they might disappoint a bit, not be as lovely or as funny as I’d imagined, but the opposite was true, absolutely brilliant, the pair of them, very funny and courteous. And I still love listening to the music! Sometimes when you work on something for a while you can’t listen to those tracks for a long time, but not with them. And we got to go for dinner with them! So that was very exciting.

You recently worked on ‘Reality is Not Enough’ about Irvine Welsh. What was this like?

AS: We started cutting Reality is Not Enough in January 2023. Director Paul Sng already knew Irvine, and the genesis of the film had come about one night when they’d gone to see the Todd Haynes’ Velvet Underground doc together, and Paul had asked Irvine if he might be interested in being filmed himself. He teamed up with Edinburgh based company LS Productions and with a small crew followed Irvine Welsh all over the world for a year– Miami, Dublin, LA, Toronto, etc.

The film evolved a lot from the initial premise, which was Irvine in conversation with old friends in all these parts of the world. It gradually became more introspective, and the device we used to frame it was a controlled drug trip Irvine goes on while in Toronto at a book fest. We’re then inside his mind, and Paul cleverly filmed this using historical archive in a warehouse with Irvine wandering through, while he reflects on his life in voiceover. We paused the post production of the film for a few times, while more filming was being organised, so although it didn’t come out till August 2025 we weren’t working on it throughout. Again I worked mainly from home alone and sent cuts to Paul, and he’d come over to Glasgow and perch on the uncomfortable chair in the living room with a tiny table, no mod cons other than a plate of cookies, and go through notes with me. Paul is a very collaborative director with a positive attitude and vision. He managed to enlist a fantastic array of names to read from Irvine’s work, including Nick Cave, Stephen Graham, Maxine Peake and Liam Neeson.

AS: Maxine is the connection with Tish, another film I’ve worked on with Paul, as she narrates the voiceover. The film is a profile of Northern working class photographer Tish Murtha, seen through the lens of conversations between Tish’s daughter Ella and old friends, colleagues and family. Tish was already in post production with my good friend, Edinburgh based editor Lindsay Watson cutting it. During one of the longer breaks in Irvine I was brought on to make a 60 minute version, then it was wisely decided that that would essentially bastardise the film so it never happened. However the film kept evolving after that so I was lucky to be able to carry on working on it till the end. Tish herself was never recognised properly in her day, and Ella, force of nature that she is, has ensured that this has been rectified and Tish’s work is now in the permanent collection at the Tate. Interestingly I’ve read interviews with Ella and also with Irvine Welsh, and both said “there’s no one else I would let tell this story”, which speaks volumes about the level of trust they had with Paul (and also Jen Corcoran, Producer of Tish and Sarah Drummond, Producer of Reality).

The great thing about both of these projects is that they had two brilliantly intuitive composers attached, Alex Hamilton-Ayres on Tish, and Donna McKevitt on Reality. I don’t have a great musical vocabulary but each were geniuses at interpreting what was required at each level of the score as it went backwards and forwards with each cut.

Can you tell me what you’re working on next?

AS: Synchronicity – again it plays a major role here! I’m currently working with Grant again on not one, not two, but three feature length docs spanning the arts, music and culture scene in Liverpool from the early 70s to the mid 80s. This project has a long genesis. The very first time I met Grant – we met in Mono for a coffee – he was outlining what turned into BGD and I remember mentioning to him that it was odd that the Zoo Records story had never been properly told. That was that. For the moment.

A few years later the idea was resurrected. Grant by this time knew Dave Balfe and Bill Drummond, and I put him in touch with a friend of mine Paul Simpson from the Wild Swans, who is not just a brilliant musician but also a great raconteur, and he knows everyone as he was at the centre of that scene. (His memoirs Revolutionary Spirit: A Post-Punk Exorcism came out last year and are well worth a read). Again, that was that. Then a couple of years later some short film clips appeared in my inbox, sent by Grant – he’d been filming Paul in Liverpool. And also filmed, rather wonderfully, Bill and Dave in bed like Morecambe and Wise, reliving their 40 year friendship, talking about the Zoo story, all the personalities involved and generally winding each other up. Charming and fascinating.

Since then Grant has enlisted many other great characters such as Will Sergeant and Les Pattinson from Echo and the Bunnymen, Mick Finkler and Gary Dwyer from the Teardrop Explodes, Pete Wylie, the indomitable Queen of Eric’s (and indeed Liverpool) Jayne Casey, Andy McClusky, Paul Rutherford and many more. Not only that, Grant then unearthed the story of the heart and soul of the predecessor to the Eric’s/Zoo era – The Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun, an arts hangout based in a converted warehouse in the famous Mathew St, erstwhile home to the Cavern. It was started by poet and Jungian disciple Peter O’Halligan. [Carl] Jung had never visited Liverpool but in 1927 dreamed of finding himself in this “dirty sooty city”…”Liverpool is the Pool of Life”. He believed that synchronistic events are a reflection of the subconscious, that coincidence and chance can be meaningful, that things can have more than one way of making sense. Hence the inclusion of ‘Pun’ in the name of the School. And it would see the likes of Jim Broadbent take to the stage with Ken Campbell’s 23 hour long staging of Illuminatus!. Carol Anne Duffy and Bill Nighy hung out there. Letter to Brezhnev director Chris Bernard started as stage manager there. Bill Drummond was a humble carpenter, manufacturing complicated 3D collapsible sets from virtually nothing but sheer imagination. It is a truly fascinating tale, we have incredible film archive from Chris Bernard to illustrate it too, and Peter is a unique other-worldly character with a vision and a philosophy, but he is a do-er as well, he makes things happen, same with Bill Drummond. They have wonderful magical ideas and make them happen. Very inspirational.

Anyway, we have no money or funding so I’m not sure if we’ll ever get these finished but at the mo the first and third films are at a good rough-cut stage. We just need a philanthropist to help ease the way!

With thanks to Angela Slaven.

‘Team Griffin’ – Photograph copyright Douglas Corrance, used by kind permission

Angela Slaven editing and Angela with Brian Griffin – Photographs copyright Michael Prince, used by kind permission.

All other photographs courtesy of Angela Slaven.

Leave a comment