Malcolm Ashman is known for his work as a landscape artist and for his portrait paintings. His landscape pictures encapsulate the beauty and shimmering magic of the countryside, while his portrait paintings reveal the character of the subject. Ashman also works in several different media to communicate his ideas with an audience. He is a sculptor, a print-maker, and a photographer.

Ashman knew from an early age he was destined to become an artist. It was intuitive. Just as Barbara Hepworth noted about her own artistic vision: “Perhaps what one wants to say is formed in childhood and the rest of one’s life is spent trying to say it.”

Raised in a rural environment, Ashman’s working-class parents had little knowledge in how best to help their son develop his talent.. Necessity meant he used whatever stray materials were to hand. He honed his talent through self-belief and hard work.

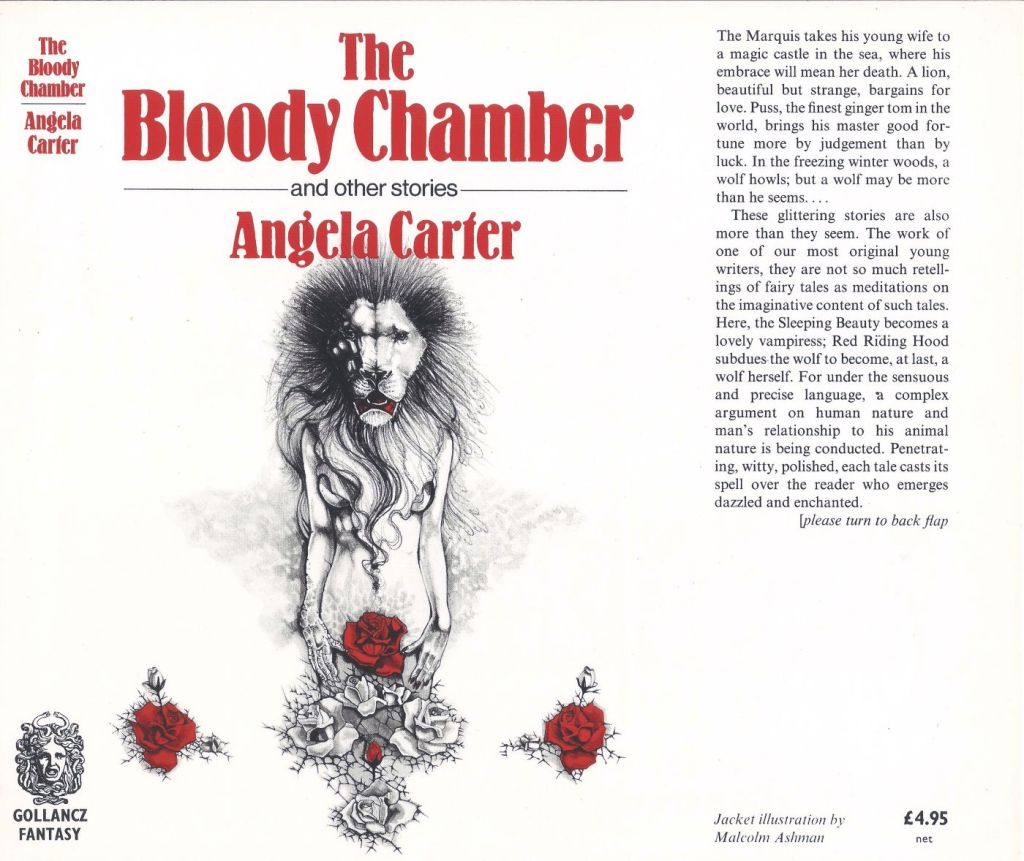

After studying graphic design and illustration at the Somerset College of Art., Ashman designed the book cover for Angela Carter’s novel The Bloody Chamber. This led to a career illustrating books including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass. Ashman continued to paint which led to his first group show. Since then, Ashman has had many solo exhibitions and received numerous awards.

Can you tell me about your childhood and your first interest in making art?

Malcolm Ashman: I was born into a rural working class family, an only child until the age of seven. My parents had no knowledge of anything connected with the arts but were quite practical in domestic matters. My grandfather lived with us and I spent all my pre-school years with him. I had acquired all the skills and daily routines of a 70 year-old by the age of five.

He encouraged me to paint, draw, garden and appreciate nature, all the pursuits I still enjoy today.

The materials for making art were all to be found in the home; scraps of wood and fabric to make objects and puppets, old magazines for collage and remnants of house paint. I was allowed to paint and draw on my bedroom walls and made the most of this. My parents, though they didn’t know how to help, didn’t discourage me which, looking back, was the best thing they could have done for me.

You have said you wanted to become an artist from the age of four – what exactly did you mean, understand or know about this ambition and how did you think you would achieve it?

MA: As a four-year-old making work felt good, it was the thing I could do best and I was happy for this to continue. In 1960 small children weren’t usually asked what they were going to do with their lives. In fact they weren’t asked anything at all as I remember.

What sort of artworks did you make as a child? Did you have art class at school? What did you learn from this?

MA: I went to a small village school which had a progressive headmistress though I didn’t realise it at the time. She recognised strengths and prioritised individual needs. I was an oddball with no love of the team spirit so she didn’t force the issue. She gave me confidence to follow my own ideas and encouraged experimentation. We kept in touch until she died in the late 1990s.

Art can be about making sense of the world – what was it you wanted to make sense of?

MA: Aged eleven I went to a local grammar school where all the things I loved were pushed aside, individuality was out, fitting in was demanded. It almost broke me. After a wonderfully supportive start, education had become a minefield. I realised that the world didn’t make sense and sometimes they really are out to get you. Art was a place where I could cling to any shreds of self confidence that remained.

You have said ‘Whatever I make, landscape or portrait, it’s saying something about me. Ultimately the artist is the subject…’ Can you discuss this?

MA: Everything I or any artist makes is the result of thousands of decisions, it’s all in my head so ultimately it’s all me. This personal short hand is vast and translating it into the spoken word is nigh on impossible for me at least. Hopefully a few people will catch my drift. I’m not explaining this very well which rather proves my point 🙂

Where did you go to art college and did you enjoy it? What did you learn from your time there? What sort of friendships did you make?

MA: Halfway through my time at grammar school, it became a comprehensive, amalgamating with an adjacent secondary modern. Immediately I had access to a well stocked art room and committed teachers. Encouraged to think about art college I eventually managed to secure a place after a number of rejections.

It wasn’t the experience I’d expected but to be fair I was dealing with some personal issues which were more important. On the whole I enjoyed many aspects of my three years there but it became clear that formal education wasn’t working for me.

I’m still in touch with one friend from that time, in fact we’re having a show together later in 2025.

‘Leaving art school was liberating and daunting’ – what do you mean by this and how did you become involved in book illustration?

MA: I was glad to move on though trying to find freelance work was daunting. I’d worked in the graphics department at college but I was not interested in the subject so for the last year I’d worked on illustration briefs I’d set myself. The results were often bizarre and regularly failed to communicate anything to my fellow students.

No one had suggested being a painter, in fact the fine art tutors had been openly hostile and I’d fled to graphics to escape them.

During the last six months there I made many appointments with various art directors and artists agents in London. I met some wonderful people during this period and many small acts of kindness kept me going. By the time I left college I had some experience of the wider world which helped enormously. I didn’t want to live in London so getting jobs was slow.

Tell me about your work as a book illustrator – which in particular are your favourites?

MA: Fantasy subjects were quite big in the 70s and one of my first commissions was from Victor Gollancz, the first edition cover artwork for Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber.

This is an early favourite, all the elements were suggested by Angela but the interpretation was left to me. Clearly there were possibilities for the future.

MA: Within a year of leaving college I met a group of professional painters and sculptors who invited me to exhibit with them. I visited their studios and learnt more in six months than three years of art education.

Some years on I had my first solo show of watercolour and gouache paintings at a gallery in Bath and by chance the director of Paper Tiger publishers happened by as the show was being hung. He invited me to work on a project of my choosing which they would publish. I’d bought many of their books when I was a student and this was an unforeseen and wonderful opportunity. Over the following eight years I worked on four book projects with them. The final publication Fabulous Beasts is my favourite.

Its size and format is the same as many of the fantasy books I’d bought years before, it sits on my book shelf alongside them.

Each book I worked on was, for me, a collection of individual paintings so I always felt calling myself an illustrator didn’t quite fit. After the final book everything changed.

What happened?

MA: Up to this point I’d painted from observation often en plein air and definitely naturalistically using watercolour and gouache.

During the summer 1996 I walked the Lyme Bay coast path with a small group. I took paper and pens so I could draw along the way but the rest stops were short so I quickly learnt to simplify the landscape, basic shapes and written notes for colour.

This coincided with with a friend giving me a box of oil paints which I’d never used before. The resulting paintings were by and large disliked by most people but some sold and gradually I gained a degree of control over the new medium and a few galleries started showing the work.

You have said painting a portrait is like a collaboration between the artist and the sitter – can you please elaborate?

MA: In 2004 I rented studio space at Bath Artists Studios. It was similar to my earlier experience of meeting a large group of professional artists, it revolutionised my approach.

I developed ways of working and organising ideas that made total sense to me.

There were a number of portrait artists working there and I began to explore possibilities.

Spending time with a sitter inevitably brings other ideas to the work.

There’s another voice to listen to and I found I liked that. I’d never got the hang of other people try as I might. I like people but I like them one at a time. Painting portraits can create an immediate connection if you’re lucky. Small talk can quickly evolve into very personal conversations. The calm of the studio environment has a feeling of the confessional so I was often told.

MA: These conversations influenced the way I presented the sitter and I was always happy to consider any ideas they had for the work.

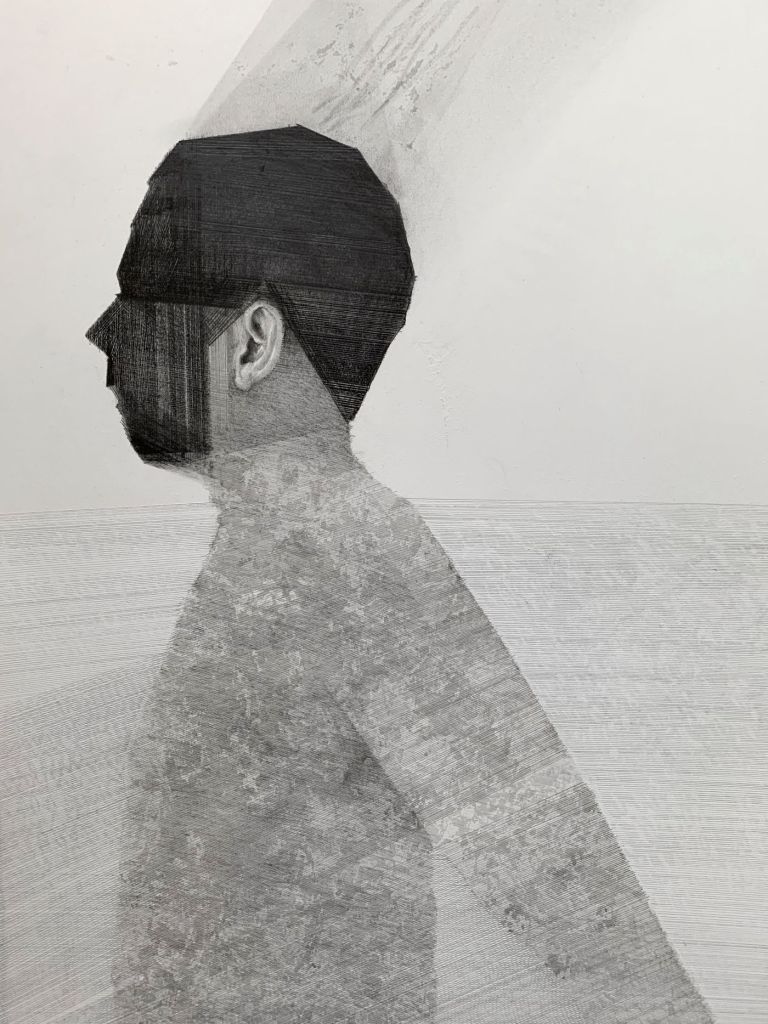

In 2020 lockdown I began a series of imaginary portraits without sitters and very much like my approach to my landscape paintings, memory based. These were tiny paintings and I call them Small Heads. I’m still working on this series.

How do you paint? Tell me about your processes – the use of colour, how you block out a canvas, how do you start? Is it daunting to put a mark on canvas?

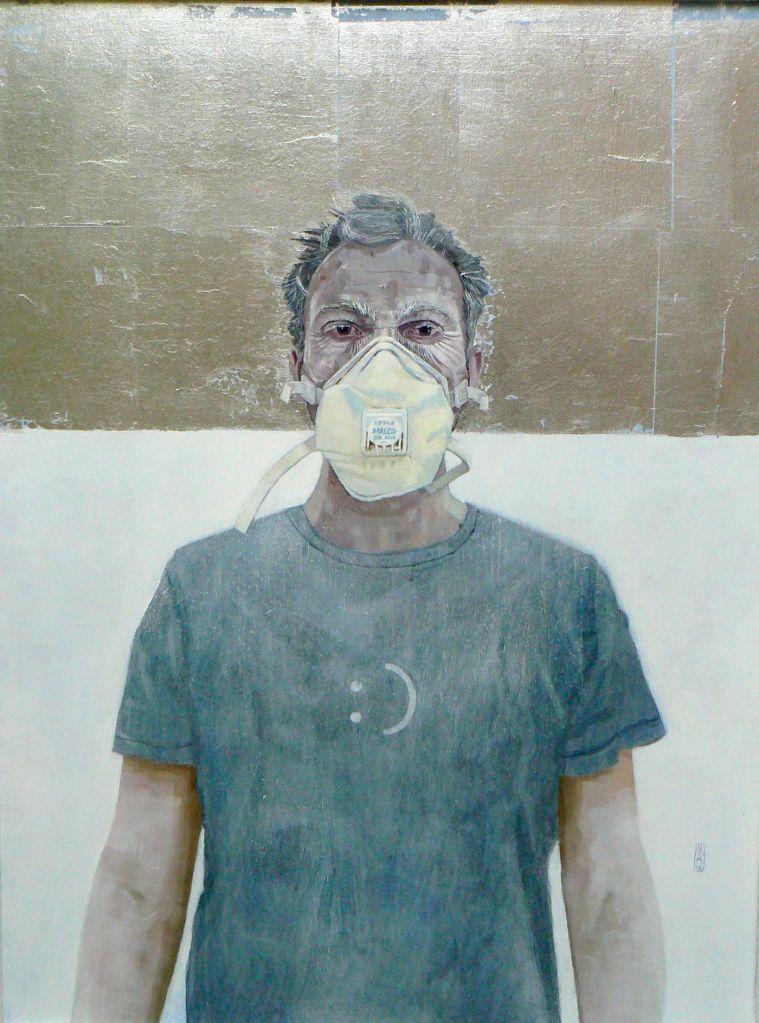

MA: Over the years my process has evolved. I’ve worked in many different mediums and disciplines, but I still make simple drawings for both landscape and portrait paintings. Once I begin the work I rarely refer to them but they get me started. I painted with water based paints in my early career then oils. I switched to acrylics after I began to have health issues from the solvents. I miss the luminosity of oils but I prefer to breathe easy. I like working on panels, scraping and sanding the surface. I have used canvas but it requires a less aggressive handling also I’m rubbish at stretching.

I’m never daunted by a ‘blank canvas’. I block out the basic shapes drawing with a brush then underpaint the entire panel. I paint in layers but try to leave some of the underpainting. Colour is instinctive, if it doesn’t work it can be changed. Too much theory gets me down.

What is a typical working day like?

MA: I don’t have a studio routine though I always work at weekends. I like to set myself projects which I switch between during the week. I’m becoming increasingly aware of time passing and my focus is growing more intense. I spend an hour on the garden at some point in each day, it’s the only activity that stops me overthinking.

Art is a process of trial and error – is this true? What do you learn from this? When do you know something is right?

MA: I’ve reworked many paintings several times, often years apart. I’ve cut down work to find a better painting and used leftovers for collage. Knowing something is right is sometimes wrong, it’s of the moment and can change. I’ve destroyed many paintings that I thought were right but ideas and skills improve over time.

I have a greater confidence than I had twenty years ago, I’ve put in the hours and I think it shows.

I often work with pencil or ink. black and white with no colour. I feel comfortable with this and I sometimes like to put my feet up and go with it but colour has always been a challenge and has certainly been a case of trial and error over many years. This preoccupation runs through everything in my life painting sculpture, gardening and interiors. I’m working on a new series of paintings for an exhibition later in the year that reference my landscape work but pared down compositionally and focusing on colour relationships in a more abstract way.

Tell me about your landscape art? What attracts you to a certain location?

MA: My early influences were the nature paintings of Tunnicliffe via the Ladybird books of the seasons and I studied these images in detail. Interestingly I never bothered much with the text, the paintings had so much much more to offer.

These books made me look to the countryside for my own subject matter. It stayed with me. I’m drawn to the wilder places, the West Country moors and the coast have always been favourite starting points. I suppose it’s the familiar but I’m always happy to be surprised. As I’ve said I work from small drawings often made in nature but the shapes of landscape are so much part of me now I can call on them at any time.

You are a multimedia artist – can you talk about your sculptural work? Where do your ideas come from? How would you describe the conversation you are having with your audience?

MA: I’ve always made 3-D pieces but it’s only since Covid that I’ve started showing them publicly.

I always start with donated materials and ‘play’ with them until an idea begins to form. In the early days I used my parents leftovers, later odds and ends from other artist and friends. I have an ongoing piece that invited everyone to donate a small item to be included, it has the appearance of a roadside shrine. I made it as an interactive piece for open studios but it continues to attract offerings many years on.

Currently I have several works in a show, Connecting Threads, at the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol. I’ve been working on these for the last five years.

In 2020 I’d helped clear the house of a relative, 90 years of collected stuff. She’d been a maker of all things domestic: clothes, soft furnishings, embroideries and tapestries. I couldn’t bring myself to throw anything away so continued using her collection of as yet unused materials, though in a very different direction. I’ve always been fascinated by the point where the man-made meets the organic, dereliction and neglect offer interesting starting points. The latest pieces are neither one nor the other, initially they have the appearance of ‘creatures’ but they also have architectural elements.

MA: I’ve made these pieces for myself without any thought of an audience. Truth to tell this has always been so but these new pieces have taken this further and there’s definitely an air of defiance in them. I’ve no thought of selling or pleasing anyone other than myself.

This current show will determine if there is a conversation to be had but does it really matter?

Tell me about your photography and print-making.

MA: In 1962 I took a series of photos of my parents on the Downs in Bristol after we visited the zoo. They were black-and-white and slightly blurred but quite recognisable. I was extremely pleased with myself. This began my relationship with photography.

Over the years I’ve tried to master the art but the process felt remote and vaguely scientific. I have patience but not for this then the digital revolution came along.

Instant success or failure, no complex processing or waiting. It felt more like the drawing or painting process, wrong decisions could be put right quickly.

With my first digital camera I spent several years photographing people at the same time I was exploring the painted portrait. The photographs were a different proposition, immediate and often unposed. Here the sitter had the same control if not more than I did. I have a small collection of old photo albums bought at sales with no information about the photographer or the photographed. I’m intrigued by them. Maybe my aim with the digital project was to set up a future mystery for someone.

I admire printmaking and printmakers. I’ve attempted all aspects of the discipline but I’ve never formed an enthusiastic connection. There are so many rules and I don’t have the right temperament.

In 2014 I met, via the good old days of Twitter, a Norwegian printmaker, Inger Karthum. She was an etcher but had embraced digital printmaking in recent years. We decided to see if we could collaborate on a series which collaged elements of both our work.

This was a very important time in my life and although we haven’t made anything together for some time, we continue to meet and compare ideas which most definitely influences my own work.

What artists, books, music or even films have influenced you as an artist?

MA: Everything that has passed before me has been an influence both positive and negative.

The Tunnicliffe Ladybirds set me on the creative path followed by early Marvel comics, CS Lewis, Alan Garner and especially John Wyndham. I like fantasy and sci-fi that also contain strong elements of the everyday.

Poirot and the Carry On team got me through difficult times in my teens. Characters who didn’t quite fit in were good role models, doing what they did best despite pressure and disapproval kept me on track.

Later I enjoyed stories by MR James and HP Lovecraft, again the combination of the fantastic and the ordinary, very much part of my latest sculpture series.

These days I find reality more interesting than fiction. I prefer published diaries and search for helpful advice to get through, as Victoria Wood says in Pat and Margaret, “this sod of a life.”

Since the Internet I continually discover artists I admire, there are so many talented individuals who keep me focused and ever hopeful. The dedication and skill of others is infectious in the best possible way.

Looking back, everything I’ve done though primarily for myself has been an attempt to find a way to talk to other people against difficult odds.

With thanks to Malcolm Ashman.

All images copyright of the artist, used by kind permission.

Portrait of Malcolm Ashman by Anne-Katrin Purkiss.

Leave a comment